Altered Gravity Perception: Why Some Dizziness Is Not Vertigo

The Ancient Sense That Grounds Us

By Dr. David Traster, DC, MS, DACNB

Co-owner, The Neurologic Wellness Institute

Boca Raton • Chicago • Waukesha • Wood Dale

When most people hear the word “dizziness,” they picture spinning rooms and twisting horizons. They imagine the classic sensation of vertigo — a world that rotates violently around them. But for millions of people, dizziness takes a different shape. They feel like the ground is gently tilting, like their body is rocking on unseen waves, like a subtle but constant gravitational tug is trying to pull them sideways. They describe floating, lightheadedness, bobbing, drifting — a deep and disorienting sense that something in the environment or the body has lost its anchor point.

This second category of dizziness, the kind without spinning, is often misunderstood. It slips through conventional testing. It gets mislabeled as anxiety or dismissed as “nothing to worry about.” And yet this form of dizziness can be profoundly disabling. To understand why it happens, we have to go back in time — way back. Before dinosaurs. Before trees. Before bones.

We have to return to the origin story of gravity itself… and the tiny organs inside your inner ear that learned to listen to it.

The Gravity Keepers

Deep inside the inner ear are two small, unassuming structures: the utricle and the saccule. Each contains microscopic crystals called otoconia — grains of calcium carbonate that are about the size of dust. As you tilt your head or accelerate in a straight line, those crystals shift, bending hair cells beneath them that send electrical signals into the brain.

These organs are called the otoliths. And without them, you would have no idea which way was up.

Long before mammals existed, before limbs evolved, before life ever walked on land, primitive aquatic creatures needed these sensors. Jellyfish-like organisms relied on simple gravity sacs to keep themselves oriented in the ocean’s shifting currents. If they lost track of “up,” they’d drift into danger. Gravity, from the very beginning, dictated survival.

Those ancient sensors never left us. They evolved into the utricle and saccule we carry today. The otoliths are older than almost every other part of your sensory system. They are history tucked into biology — tiny fossils of evolutionary wisdom.

Life in a Vertical World

Gravity is not just a force acting upon us — it shaped us. Every structure in the human body adapted to Earth’s pull:

• Your spine became a column, not a bridge.

• Your blood vessels learned to fight upward against pressure.

• Your reflexes developed to keep your head level even when your feet stumble.

Remove gravity, and the body unravels. We see this in astronauts:

• Bones and muscles weaken shockingly fast.

• Fluids migrate toward the head, forming puffy faces and congested brains.

• Balance and orientation systems become confused, leading to dizziness and nausea.

Gravity is an ever-present training partner, strengthening us simply by being unavoidable.

Even a momentary mismatch — when gravity feels wrong — can shake the brain to its core. Because the brain expects gravity to behave perfectly. When those expectations are violated, dizziness emerges.

A Delicate Conversation in the Dark

The vestibular system is always asking:

Are we moving? Or are we tilting?

The semicircular canals detect rotation.

The otoliths detect gravity and straight-line motion.

But the otoliths have a problem:

They cannot tell the difference between tilting your head back… and accelerating forward in a car.

Lean your body back.

Or blast off in a rocket.

To the otoliths, these are identical sensations.

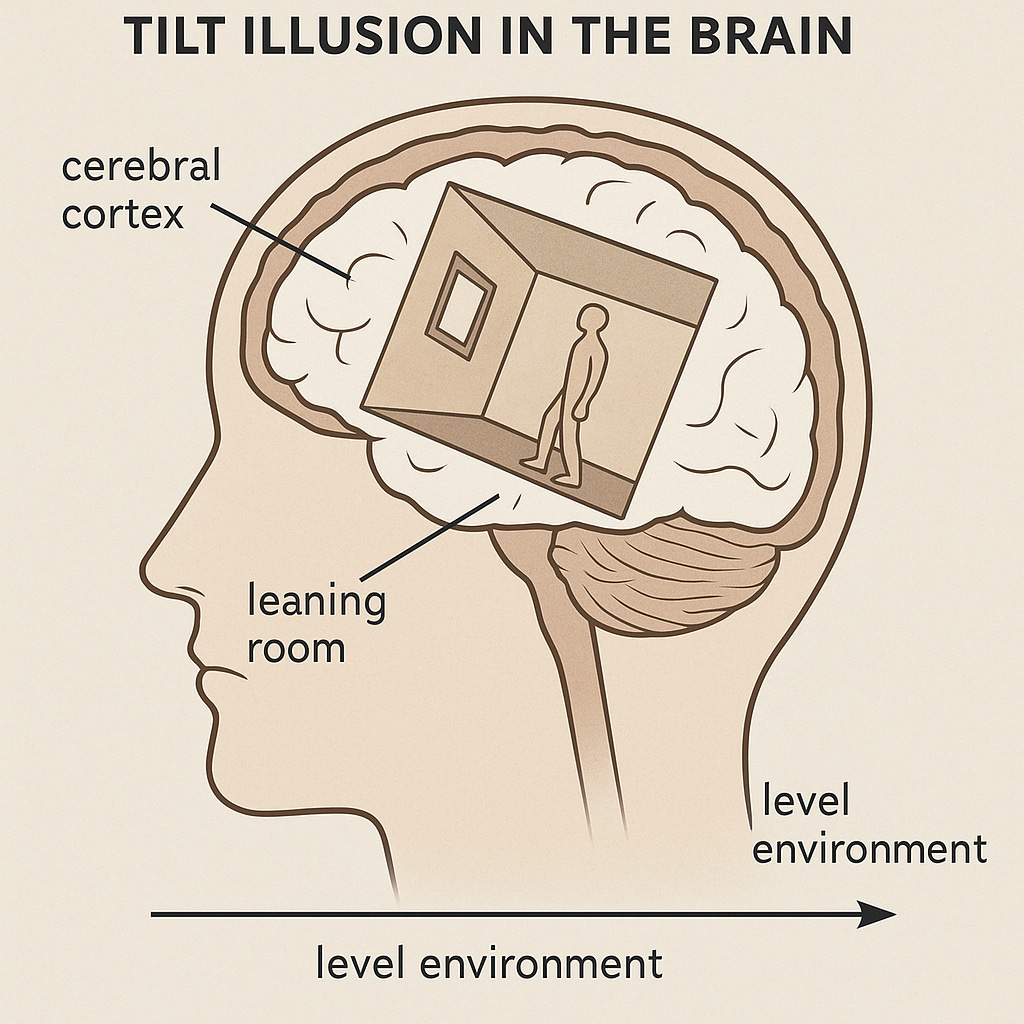

The only way to figure out the truth is to integrate data from multiple systems — the canals, vision, and proprioception — inside a beautifully choreographed neural network that includes the brainstem, cerebellum, thalamus, and cortex.

In a healthy brain, this integration is flawless. Gravity feels rock-solid. Your balance feels effortless. The world stays stable even as you move.

But when the integration falters — after an injury, an infection, an illness, or a period of high stress — gravity becomes uncertain.

When Gravity Feels Wrong

Patients with otolithic dysfunction rarely spin. Instead, they describe:

• Rocking or bobbing, as if returning from a long boat ride

• A subtle tilt in the world — walls that lean, floors that slope

• A pull or push sensation, like an invisible magnet shifting their body

• Chronic lightheadedness without fainting

• A drifting imbalance, especially in darkness or busy visual environments

The brain tries to compensate. It tightens muscles. Over-relies on vision. Forces conscious control over movements that should be automatic. But the longer the brain leans away from vestibular trust, the more fragile balance becomes. This creates a feedback loop, and dizziness becomes a daily companion.

Many patients are told their symptoms are psychological. Yet the cause is profoundly physical: a mismatch between ancient gravity sensors and the brain’s interpretation of their messages.

How the System Breaks

Why does central otolithic processing fail? There isn’t one answer:

• Post-concussion changes that disrupt sensory fusion

• Vestibular neuritis or BPPV leaving maladaptation behind

• Cerebellar or brainstem network dysfunction

• Excess reliance on vision (often after vestibular injury)

• Autonomic dysregulation reducing blood flow to the brain

Regardless of the path, the final experience is the same:

A nervous system that no longer knows how to trust gravity.

Rewiring Stability

The most encouraging truth is this:

These symptoms are not permanent.

The brain can relearn gravity through neuroplasticity.

Rehabilitation strategies include:

• Vestibular exercises that target otolith–canal integration

• Balance training that challenges sensory weighting

• Gaze stabilization and head-tilt/translation drills

• Dual-task therapies that reconnect cognition and movement

• Neuromodulation techniques that enhance adaptation

• Lifestyle support to quiet inflammation and regulate the autonomic system

When patients engage in the right program — one tailored not to a diagnosis but to their individual circuitry — the transformation can be dramatic. The ground becomes firm again. The body reclaims its native equilibrium. The brain rediscovers “up.”

Finding the Floor Again

Non-vertiginous dizziness is real. It is measurable. And most importantly, it is treatable.

The otoliths may be ancient, but their job is urgent — to keep you anchored in the universe. When their signals are misread, your entire sense of being can feel precarious.

But these systems are plastic. They can be restored. The feeling of drifting through life can shift back into the solid experience of inhabiting a body in gravity.

These crystals in your inner ear have been guiding animals for hundreds of millions of years. They guided you from the moment you took your first breath. Even if today you feel unsteady, those ancient sensors are still there… ready to help you find your balance again.

References (ADA format, no links)

Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Curthoys IS. Vestibular compensation and substitution. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13(1):27-30.

Dieterich M, Brandt T. Functional brain imaging of peripheral and central vestibular disorders. Brain. 2008;131(10):2538-2552.

Cullen KE. Vestibular processing during natural self-motion: implications for perception and action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(9):661-675.

Bronstein AM. Visual vertigo syndrome: clinical and posturographic findings. Brain. 1998;121(6):1053-1068.

Furman JM, Redfern MS, Balaban CD, et al. Postural and gait abnormalities in patients with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. J Neurol. 2013;260(3):585-593.

Herdman SJ, Clendaniel RA. Vestibular Rehabilitation. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis; 2014.

Brandt T, Dieterich M. The vestibular cortex: its locations, functions and disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;871:293-312.

Manzari L, Burgess AM, Curthoys IS. Otolith dysfunction: clinical features and new perspectives. J Neurol. 2010;257(3):149-160.

Whitney SL, Alghadir AH, Anwer S. Physical therapy for vestibular disorders. Phys Ther. 2015;95(10):290-299.